South West Airfields Heritage Trust

“Preserving Aviation History for Future Generations”

RAF Chivenor

AIRFIELD HISTORY

Background

In 1935, with concern about the growing military development in Germany, there was a plan to increase the number of RAF squadrons to 163 and its aircraft to 2,549, but it was never fully implemented. The end result was just 124 squadrons equipped with 1,736 aircraft, although they were more modern. However, the bomber force was to receive over 50 percent of the overall resources, leaving maritime units making up less than 12 per cent of British air power. From a pre-

In 1937 exercises were carried out to judge the surface fleet's ability to defend itself against submarine and air attack. No attention was given to the idea of attacking submarines from the air and it appeared the Royal Navy did not consider U-

The Air Ministry’s role for Coastal Command was to keep sea communications open for merchant shipping and prevent sea-

The onset of war led to the rapid construction of airfields right across Britain. There was also an overwhelming need for operational training and one of the new air stations selected to train crews for Coastal Command was RAF Chivenor in Devon, on the northern shore of the Taw estuary.

History

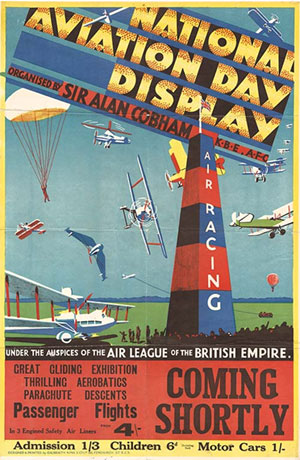

In 1933 Sir Alan Cobham had brought his 'Great Air Display' to a field between Barnstaple and Braunton, offering free flights to the first 12 people who gave the correct height of a plane that flew over Barnstaple trailing smoke. They used a site at Wrafton Gate, sometimes referred to as Heanton Court, which was to become the first licenced airfield in Devon.

Click the Panel in the far column “ NATIONAL AVIATION DAY” to see Alan Cobham’s Airshow

In December 1933 the Barnstaple and North Devon Aerodrome Club commenced flying there with two Gipsy Moths along with a Desoutter that Mr J E D Scott operated for air-

The airfield, by then known as the Barnstaple and North Devon Aerodrome, was officially opened on 23rd June 1934 by Bob Boyd and ‘Tommy’ Nash, a former RFC pilot, who was a member of Cobham’s Flying Circus. Bob Boyd commenced operating a service to Lundy using a de Havilland Dragon, but after a landing accident on the island had left it badly damaged, it was replaced by a GAL Monospar and a Short Scion.

A scheduled service under the title Atlantic Coast Air Services commenced in April 1935, but two years later the name was changed to Lundy & Atlantic Coast Airlines. With the coming of war, the service to Lundy ceased operating and the civilian aerodrome at Wrafton Gate was closed in the spring of 1940.

The opening of the Barnstaple and North Devon Aerodrome Bob Boyd & ‘Tommy’ Nash

Chivenor Airfield

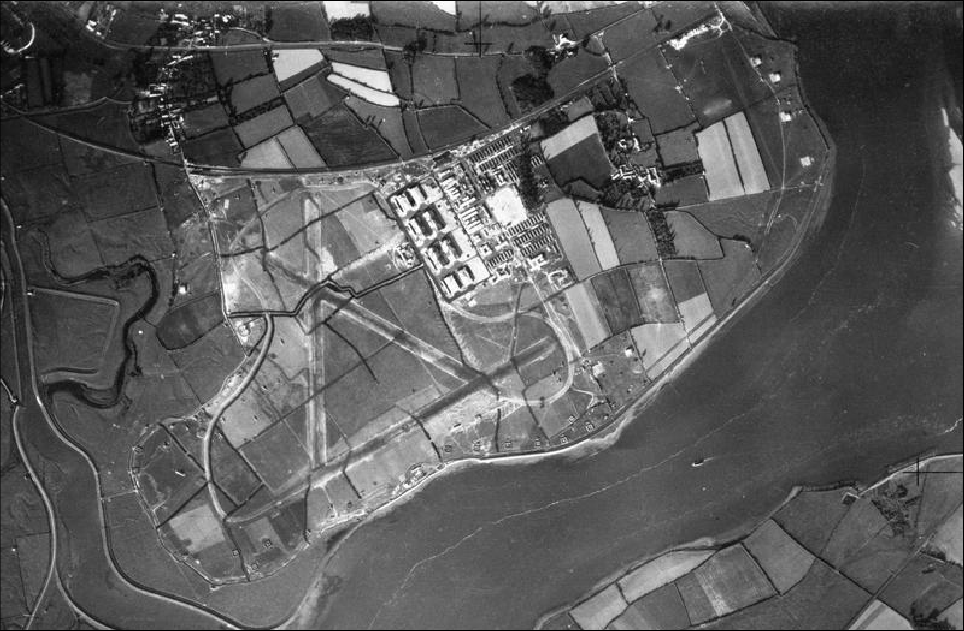

In February 1940, in response to a contract placed by the Air Ministry, George Wimpey Ltd began construction of a major airfield on the site of Chivenor farm just to the west of the Barnstaple and North Devon Aerodrome. It was laid out in a standard Air Ministry triangular runway configuration set thus, 09/27 -

Chivenor airfield in 1941 with mock ‘road and hedge’ camouflage

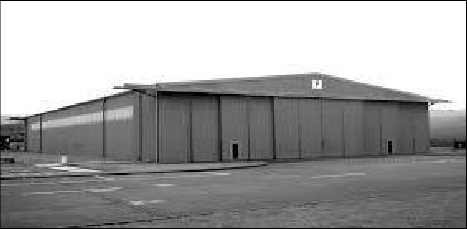

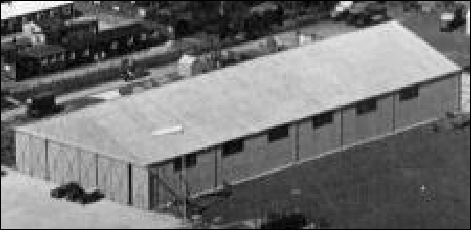

There were eight hangars, built in two parallel rows – 4 Bellman type and 4 Hinaidi type.

Bellman Hangar Hinaidi Hangar

RAF station Chivenor was commissioned on 25th October 1940 within 17 (Training) Group, Coastal Command. It retained the old grass airfield at Wrafton Gate as a satellite and the former civilian hangar and the airline staff became a part of the Civilian Repair Organisation, overhauling and repairing light aircraft requisitioned for the RAF. However, within a year it was realised there was a need for longer runways at the new Chivenor airfield, along with more aircraft dispersal and marshalling areas. Because of the boundary limits imposed by the adjacent estuary, that could only be achieved by extending the airfield to the east. It meant the site of the old Barnstaple Aerodrome would be swallowed up by the expansion. The runways continued to be progressively extended and by 1944 the east-

A recent photograph of Chivenor, from the Devon Airfields Index, shows the area occupied by the former Barnstaple & North Devon Aerodrome at Wrafton Gate outlined in red and the blue outline shows the area of the original buildings. The yellow lines mark the original limits of the runways.

THE OPERATIONAL TRAINING ROLE

The first detachment based at Chivenor was 3 (Coastal) Operational Training Unit that arrived on 27th November 1940. Operating Avro Ansons and Bristol Beauforts, it was intended they would be joined by Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys and Vickers Wellingtons, but the airfield infrastructure had not been completed and they were deployed elsewhere. extended to 2,000

On 15th April 1941, Chivenor received a visit from the Luftwaffe when it was attacked by five Heinkel 111 bombers that dropped high explosive bombs and incendiaries. The raid had only lasted for twenty minutes, but it put the airfield out of service for some days and damaged nineteen aircraft – 3 Beauforts, 10 Ansons, 5 Blenheims and a Fairey Battle.

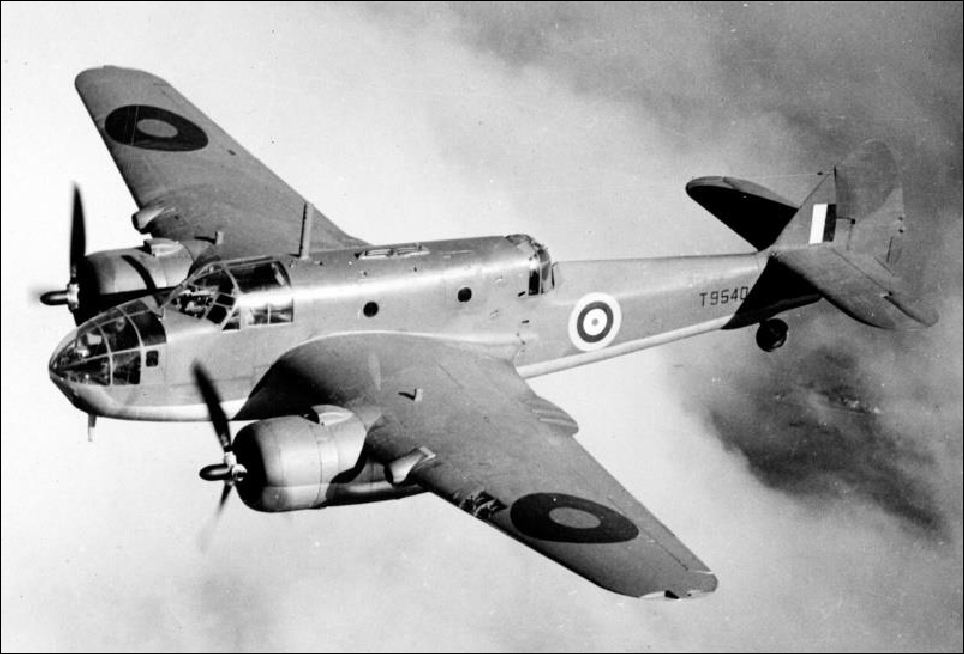

As the need of aircrew for Coastal Command continued to grow, it was decided operational training at Chivenor would be solely for Beaufort crews. In July 1941 that role was taken over by 5 (C) OTU, but the task remained unchanged. It continued to run courses lasting eight weeks, taking pilots, navigators and radio operators from basic training and developing them into integrated crews prior to being posted to operational Beaufort squadrons.

Bombing and air firing practice was conducted at a range in Morte Bay. Results of the ‘attacks’ were determined from an observation post on the cliff by Putsborough.

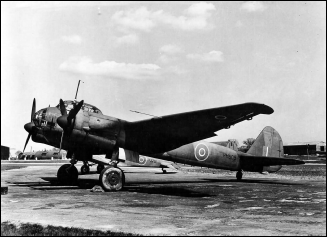

The Bristol Beaufort was a twin-

The prototype first flew on 15th October 1938, but a lack of power from the Bristol Perseus engines and reliability issues dogged the initial production batch. Later aircraft were fitted with the more powerful Bristol Taurus XX engine.

Avro Anson

Bristol Beaufort

The observation post and directional arrow at Putsborough

The Bristol Beaufort

Flown by crews trained at Chivenor, Beauforts saw service on operations in Europe and North Africa. Operating from bases in Egypt and Malta, they helped to disrupt German supply lines, sinking tankers and cargo-

In the evening of 26th November 1941, a group of Beauforts were flying practice circuits at Chivenor when another aircraft joined them. It landed and came to a stop near the control tower where the duty staff were amazed to see it was a Junkers 88 with Luftwaffe markings. A sentry fired a warning shot and the crew were taken prisoner.

Returning from a raid on ships in the Irish Sea, the bomber had been lured off course by British Meacon radio transmissions that disrupted its homing signal. In the confusion, the crew mistook the coast of North Devon for France and the pilot landed at what he thought was a ‘friendly’ airfield.

The Junkers became part of the RAF’s 1426 Enemy Aircraft Flight, which evaluated captured German aircraft – the unit was known as the ‘Rafwaffe’

The captured Junkers 88 with RAF markings & below

Throughout 1941, operational training at Chivenor continued with Beaufort conversion and crewing conducted to the same tight schedule. With such intense training there were bound to be consequences. When 5 (C) OTU departed Chivenor in May 1942 it, and its predecessor 3 (C) OTU, had lost 33 aircraft due to accidents that resulted in the deaths of 64 airmen and two civilians.

Nevertheless, in the eighteen months the two units were based at Chivenor, they had provided hundreds of trained aircrew for the Beaufort strike squadrons of RAF Coastal Command.

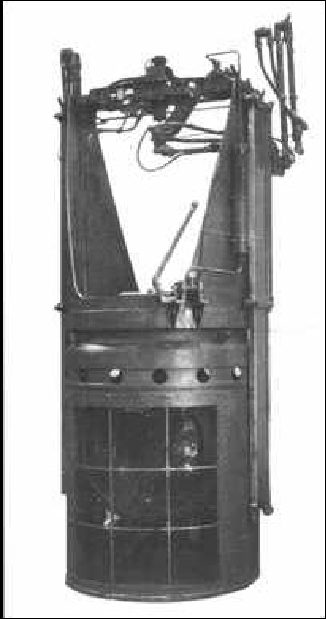

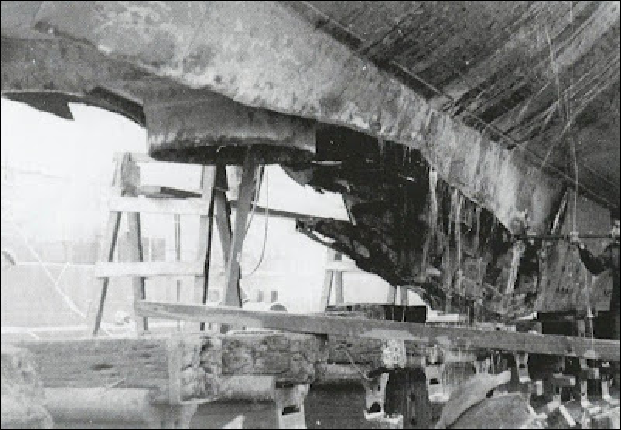

A Wellington aircraft with the Leigh "dustbin" under the fuselage.

The Leigh Light Trials

Acknowledgement of the threat from U-

The threat posed by U-

They also needed to come up to recharge their batteries. To avoid detection, running on the surface was preferably done at night. By 1941 Britain had developed an air surface radar system, ASV2. Carried by aircraft of Coastal Command, it was capable of detecting vessels on the surface.

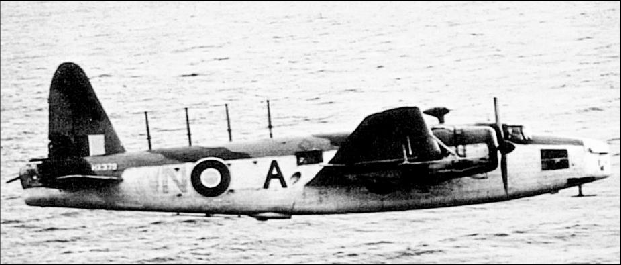

Vickers Wellington Mk 8 with ASV2 radar

Although the development of ASV2 radar was a breakthrough, it had the shortcoming that contact was lost when the aircraft got to within a mile of the target. That did not matter in daylight, but it was a serious disadvantage at night. One solution considered was to fit a searchlight to the aircraft

An Example of retractable Leigh Light

The chosen option was the brainchild of Wing Commander Humphrey de Verd Leigh, a former pilot, whose idea was to use a retractable spotlight suspended below the belly of a Wellington. It utilised the hole in the fuselage designed to house a ventral gun turret. Fraser-

In January 1942 four Wellington Mk 8s arrived at Chivenor to become 1417 Flight (Leigh Light Trials). Its task was to develop effective anti-

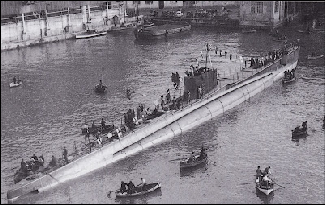

After the successful completion of trials, 1417 Flight remained at Chivenor to become the embryo of 172 Squadron. Their first attack using the Leigh Light was on 4 June 1942. The Wellington, flown by Squadron Leader J H Greswell, made radar contact at 01.30 hrs and the searchlight soon illuminated the target. It was the Italian submarine Luigi Torelli on its way from La Pallice to the West Indies. During the attack, four bombs were dropped that straddled the hull. Although badly damaged, and despite further attacks, the submarine managed to reach Santander in neutral Spain.

The very serious damages reported by the Torelli , visible after her docking at Santander, on 8 June 1942 Following the attack by Squadron Leader JH Greswell of 172 Squadron

172 Squadron’s first confirmed U-

Both Squadron Leader Greswell and Wiley Howell were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Wing Commander Humphrey de Verd Leigh

The first successful test during the morning of May 4 1941 when Leigh himself as pilot illuminated the British submarine H-

The launch of the Torelli

(from www.betasom.it )

Below at sea

Chivenor’s Ant-

Following a reorganisation of Coastal Command in February 1941, responsibility for patrolling the Bay of Biscay and the Western Approaches was taken over by the newly formed 19 Group based at Plymouth. When Chivenor moved from a training role to one of operations, it became part of it.

With the fall of France, the Kriegsmarine quickly took advantage of the docks and ports that gave access to the North Atlantic via the Bay of Biscay. In addition to the naval dockyard at Brest, U-

The first from Chivenor were carried out by 77 Squadron on 1st June 1942 and 51 Squadron the following day. Both had recently been transferred from Bomber Command and were equipped with Armstrong Whitworth Whitley Mk 5s that did not have ASV2 radar or Leigh Lights. Returning to Chivenor from its very first patrol on 1st June, a Whitley of 77 Squadron encountered poor visibility and flew into the cliff above Pilots Quay on Lundy Island. All six men on board were killed

For four months 51 and 77 Squadrons operated from Chivenor, flying a total of 535 patrols during which nine U-

Despite the initial success of ASV2 radar, by August 1942 the Kriegsmarine had come up with an effective counter measure. Metox was a radio receiver tuned to the radar’s waveband that gave submarine commanders ample warning of an approaching aircraft that could be avoided simply by the expediency of diving. That, and severe weather at the end of 1942, meant the Battle of the Atlantic became something of a ‘stalemate’.

By the spring of 1943 the advantage had swung back in favour of the Allies with the introduction of improved equipment. Early in 1943 Coastal Command received the Mark 8 Torpex depth-

The other innovation was the introduction of ASV3 radar. ASV2 used the long 1.5 metre wavelength, but ASV3 was a short-

In March 1943 172 Squadron was equipped with Wellington Mk 12s fitted with ASV3 radar, their distinctive ‘chins’ being an obvious feature. Soon two more Wellington squadrons joined them at Chivenor, 407 Squadron RCAF arrived in April and 612 Squadron the following month.

Armstrong Whitley Mk 5s of Coastal Command

Vickers Wellingtons with ASV3 radar at Chivenor

The build-

Commencing in June 1943 and lasting seven weeks, Operation Musketry proved highly successful. It involved a patrol of seven aircraft spread out on parallel courses. This was done three times a day and when contact was made, the other aircraft and the frigates were homed in on the target. By early August it had resulted in the sinking of more than 20 U-

In March 1944 304 Squadron (Poland) arrived at Chivenor to join 172 Squadron undertaking anti-

With the Normandy beachhead secure and access to the submarine pens in France now denied to U-

In November 1944 407 Squadron RCAF returned to Chivenor, joining 36 Squadron that had arrived in September. With both operating Wellington Mk 14s, they remained there until the cessation of hostilities. The last wartime loss of an aircraft from Chivenor was on 7th March 1945 when a Wellington of 407 Squadron crashed at Bideford East-

A poignant reminder of the sacrifices made by the airmen from Chivenor is the war grave cemetery in St Augustine’s Churchyard at Heanton Punchardon. Looking out over the airfield, it contains more than eighty Commonwealth war graves, most are of airmen from RAF Chivenor. Others were returned to their families, but many were lost on sorties over the sea and have no known grave. They are commemorated on the Air Forces Memorial at Runnymede.

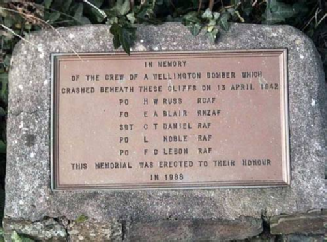

The memorial commemorating the crash of the Wellington bomber from 172 Squadron that crashed into the cliff at Beckland Bay

Below the memorial at Higher Clovelly

St Augustine’s Churchyard, Heanton Punchardon

Post War

The post war plan for Chivenor was for it to be a base for an anti-

In 1946 the station came under 11 Group Fighter Command and hosted 203 Advanced Flying School that operated Supermarine Spitfires.

In 1950 it became home to 229 Operational Conversion Unit flying de Havilland Vampires and Gloster Meteors.

In 1955 the first of the Hawker Hunters arrived and they became a familiar sight for almost 20 years until 229 OCU transferred to Brawdy in Wales.

Following an extensive rebuilding programme, Chivenor was reactivated in 1979 and became the base for BAe Hawks training fast jet pilots and navigators. Flying training continued there until 1995 when it transferred to Valley on Anglesey and Chivenor ceased to be a RAF station.

Hawker Hunter

BAe Hawk

In June 1957 a new chapter in Chivenor's history had opened when 'E' Flight of 275 Squadron began helicopter search and rescue duties. In 1958 it became 'A' Flight, 22 Squadron, which was to lead to a twenty-

Westland Wessex at Saunton Sands

In 1995 the entire complex became Royal Marine Base Chivenor that now houses the Commando Logistics Regiment, Royal Marines and 24 Commando Regiment, Royal Engineers. The main runway is kept operational for RAF heavy transport aircraft supporting the 3rd Commando Brigade.

Sources of information – text and photographs

Robert Jones

Paul Stanton

British Military History Group – Robert Palmer & Graham Moore

Devon Airfields Index

Imperial War Museum

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Wikipedia

The National Aviation Day campaign, known as ‘Cobham’s Flying Circus’, toured Great Britain, Ireland and South Africa giving many their first experience of flight.

Cobham’s Flying Circus toured between 1932 and 1935 taking 990,000 people on flights in his fleet of aeroplanes with over 3,000,000 people visiting the display.

The incredibly successful campaign encouraged the nation to become more aware of aviation and also inspired many to fly themselves.

The introduction of the Leigh Light combined with ASV2 radar had an immediate impact, denying U-

Photographs taken by the rear-

Southwest Airfields Heritage Trust © 2017

Location: Chivenor, North Devon

Opened in 1934

Currently used as a Royal Marines Base

No access