South West Airfields Heritage Trust

“Preserving Aviation History for Future Generations”

Some recently acquired photographs taken at RAF Exeter from May 1942 – June 1943. Whilst a Czechoslovakian day fighter Squadron, RAF 310, were operating from Exeter.

These photos arrived by courtesy of Dave Trevor who found them in a job lot at an auction possibly originating from a home in Liverpool.

There is some evidence they may have belonged to an ex RAF Ground Crew member, whose surname may have been Wearne ?

Added information and identification has also been provided by Tom Dolezol a specialist historian on the Free Czechoslovakian Air Force.

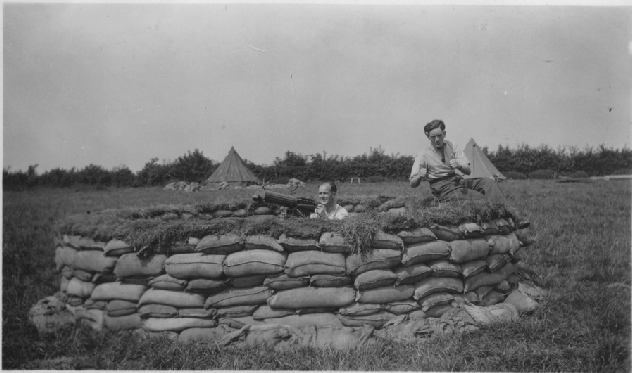

This picture below possibly taken during 1942 depicts a recently established anti aircraft pit this was at Heath House Farm. Exeter airfield had been subjected to numerous aerial strafing and bombing since 1940, Situated close to the Exe Estuary it was an easy target for the enemy to find.

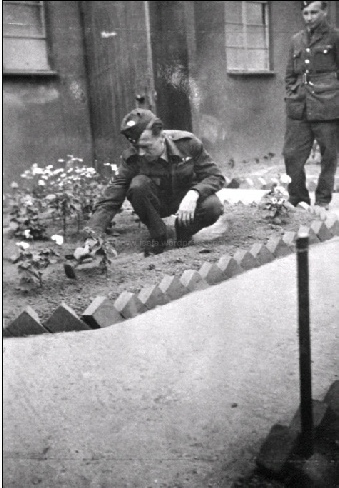

This is an interesting picture and shows the pride of the Czechoslovakians of 310 Squadron, outside of the Squadron HQ building the airmen had created a garden.

Tom Dolizel observed “The rear left hand garden shows the Czechoslovak airman’s garden, the front left hand garden shows the outline of Czechoslovakia.” The text in the top right hand corner of this garden is ‘Pravda vítězí ‘ the Cz national motto of ‘Truth prevails’

In the back ground a 310 Squadron Spitfire is parked in front of a blister hanger

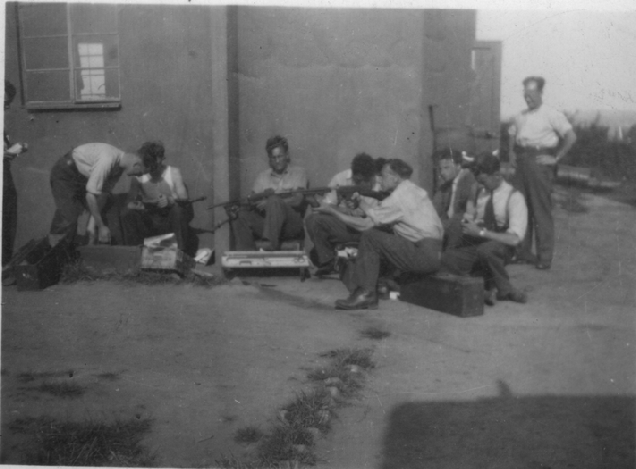

Tom’s identification for this picture

1. Lichtner Zdeněk Tom's ID 6

2. Svoboda Svatopluk

3. Fuksa Albert

4. British

5. Tomeš Ludevít

6. British

7. Juřica Alois

8. Šikl Jindřich ?

Number 4 in the photo we think may have been the original owner of the photo as he is shown in a couple of the others and Dave Trevor says there was a photo of the same person among the collection also wearing uniform listed University.

Extra Pictures From Tom Dolezol https://fcafa.wordpress.com/

Bert Strong who was in the RAF Regiment is fifth man in the middle line from the right, he served as an anti aircraft Gunner at RAF Exeter during 1940-

In the picture below also taken at RAF Exeter he is fourth man from left in the middle row.

WW2 RAF Anti aircraft Gunner Albert Strong sets up home in one of the accommodation huts after demob

Bert Strong who was in the RAF Regiment is fifth man in the middle line from the right, he served as an anti aircraft Gunner at RAF Exeter during 1940-

In the picture below also taken at RAF Exeter he is fourth man from left in the middle row.

During his service there he met and married a local girl during 1944: Eileen Coombes who was living at No 2 Council Houses, Clyst Honiton near Exeter, close to the airfield. (Better known by the locals as Honiton Clyst back in those times.)

Eileen had the misfortune of having an eighteen year old sister called Wanda killed along with James Pugh (age 26) during an air raid 12th of February 1942, when they were strafed with machine gun fire from an enemy aircraft In the vicinity of the greenhouses at Rockbeare Nurseries, where both Eileen and Wanda worked.

After Airman Bert Strong was de-

This is where their son Graham Strong was born, who has given us this information. The hut they lived in was (number 283) on “Site 3” with a postal address of Westcott Lane, Rockbeare.

Graham say’s he believes other families also lived in the airfields disused huts after the war ended. His family were re-

Graham and ourselves would love to hear from anyone who has any memories or connections with any of these events. Graham has a website where you can learn more about his family and history

Including the Coombes family who have connections at Ilminster in Somerset where Wanda was laid to rest 1942. Do go and visit his website

http://www.gstrong.co.uk/rockbeare.html

Memories of two Operations’ Room W.A.A.F Plotters, RAF Exeter 1941 -

We wish to thank David Malleson and his grandmother Miss Elizabeth Lake (now Mrs E Stevenson) who lives at Newcastle for sharing these photos and her memories. We welcome any comments and any more information about the following pictures from anyone interested.

Memories of WAAF Elizabeth Lake

Memories of WAAF Elizabeth Lake

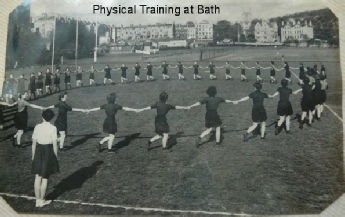

During the first two or three weeks they were tested to ascertain where their talents would be best suited, at the same time they underwent medicals and were put through their paces with plenty of drill on the sea front.

Elizabeth recalls that the W.A.A.F officers were generally a nice bunch of people who made the best of what was a pretty grim time. At the end of the assessment phase the W.A.A.F intake assembled in a cinema and were allocated their work. Their service numbers and surnames were individually called out and they were given their new posting locations, which for Elizabeth Lake was a journey by train to RAF Exeter.

She recollects that her plotting table training at Exeter was carried out away from the main operations block, which was situated at Poltimore a mile or two away from the airfield.

Once she was trained her shift pattern was something like 8am-

Then back on duty at 8am for the next shift. This all started in the worst winter for some years, it was so cold that the main water tank split open one night and the water froze in midstream to form an arc from the tank to the ground. Their accommodation was in unlined Nissen huts, each with a small stove providing the bare minimum of heating.

They all had to take turns during the night to re-

However as her photographs show, it was not all doom and gloom and as one would expect with a crowd of young ladies thrown together by circumstances of war, they knew how to let their hair down when the opportunities arrived.

These came in the form of twenty-

She left her baggage in the guardroom at the station and went to the dance, returning to Exeter the following morning with three minutes to run over the platform bridge, retrieve her baggage and then run back to catch her London bound train! When going on leave, she travelled with her two close friends, Norah Crabb and Betty ???

Rules that they had to travel in uniform were often flouted – as they used to change into civvies behind a garden wall near their bus stop. On one occasion, they emerged to find a senior W.A.A.F officer waiting for the same bus.!

A collection of pictures from Elizabeth and friends taken during 1942—1945 whilst she was stationed at RAF

Miss Elizabeth Lake was the daughter of a school headmaster and she received her call up papers in late 1941 and was ordered to be at Euston Station very early on a December morning. The station was of course blacked out and there were hundreds of service personnel milling around.

She along with the others of her intake were put on a train bound for Gloucester, this was to be part of a long tedious journey to Morecambe Bay.

Here the RAF had commandeered almost all the bed and breakfast establishments and Miss Lake and her W.A.A.F colleagues were to be billeted four to a bedroom and having to double up by sharing two single beds.

All Smiles

All Smiles

Exeter WAAF

Exeter WAAF’s outside their Quarters

Some of the W.A.A.F’s who were stationed at RAF Exeter during 1942-

Elizabeth Lake with her close friends

Exeter WAAF taken on one of their train journeys

Group Photo taken Exeter

Group Photo taken Exeter

Interesting Group Photograph taken Exeter

Another Jolly Group

In the Shadows

Meeting a friend on that day off !

Memories of WAAF Phyllis Hill

AIR FORCE PLOTTER FIGHTER COMMAND 1941-

We thank Phyllis and her son Keith Hill for sharing these memories.

AUGUST 19th 1939.

My Wedding Day aged 20 years. We were on our honeymoon when war was declared.

Returning to our new house in Devizes, Wiltshire, our first visitor was a Catholic nun with a housing officer and small girl about 8 years old, who was to be our evacuee.

Lily was a sweet, quiet, girl, not used to home comforts, and owning nothing. We bought her gifts, took her to the seaside, cinema, had her little friends to tea; could not spoil her enough.

Alas, the nuns were not happy with this change of life, and after a few months, they were all collected up and returned to the orphanage. We tried to keep in touch, but no way – a closed door.

Towards the end of 1940, my husband was enlisted into the RAF, posted to Blackpool, then to a wireless operator’s school, mostly to learn Morse code. Within a few months, he was on the high seas, destination unknown.

I decided to store our furniture, let the house, and store our clothes at my parents’, and join the RAF.

The nearest recruiting office was Bath, and I reported there. A male officer asked me a whole lot of questions – spelling, mental arithmetic and IQ; he told me that I would receive my papers and a railway warrant in a few days. I did – Gloucester was the destination, it was May 2nd 1941.

Arriving at Gloucester, there were RAF police calling “WAAF Recruits” – that was me! We were taken to a RAF lorry, I had my first experience of climbing up the tailboard, also my first lesson – be first up the tailboard to get a side seat – alas, I was on a form down the middle!

Arriving at Innsworth Lane, we were checked, shown into huts of about 20 beds, 10 each side. On each bed were three square mattresses known as “biscuits”, 3 hairy air force blue blankets, 2 unbleached sheets and a roly poly pillow filled with hay.

A sergeant entered, “stand by your beds and listen to the rules”. Lights out by 10 pm, beds stacked, washed, outside by 8 am, ready to march to the Mess. All a bit strange, but most of us slept well.

Morning arrived, we found the ablutions, nothing private here, stacked our beds blanket sheet, blanket sheet, 3rd blanket folded long ways wrapped around with the ends underneath all folds to the front, it did look neat when done properly.

Sergeant tried to teach us to “get fell in” and find our left foot to start our first march to the mess.

The next few days were a test on our stamina, drill, march, fitted with uniforms, vaccinations, tests on our brains – oh those blistered heels, NAAFI sold out of plasters, we were all limping – at this time several high tailed it back home!

About my fourth day, one morning among the sea of faces, I saw one I knew. She saw me at the same time. We fought our way together – she had just time to say “try to be a plotter”. I don’t know what it is, bit I am to be one!

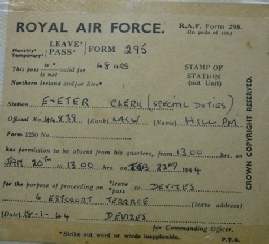

My interview time came, two male officers sat behind a desk. I boldly said “I would like to be a plotter”. “Do you know what a plotter is?” they ask. A little less boldly I said “No, but I’ve a friend who is going to be one”. Questions followed some more spelling, maths. “Would you be calm under fire?” I said “Yes”, was passed. “Clerk, Special Duties” was the title, we, nor anyone else, knew what it was!

We passed it all, were soon on a train to Leighton Buzzard, and finally arrived at a Plotters School, a building resembling a prison.

On the first morning we were shown into a large room full of maps and telephones. We had to make an oath on the Bible that we would never talk of our work, or make any notes; we began to feel collywobbles at this stage.

The teaching did prove very intensive, especially as we could not make notes – we lay in bed testing each other – I cannot remember any free time at all, but never thought of giving up.

At last a list was presented of stations needing plotters; these were fighter command operational stations.

Most girls wanted to be near London, so Colerne in Wiltshire did not receive many names. We were pretty sure we would be going there, and we were.

We said our farewells, and caught a train to Bath; here we were met, quite used now to living out of a kitbag, and climbing tailboards.

Colerne was a fairly large station of concrete blocks. We were shown into “B” Block. Outside our window, was a runway to a hanger. We were soon to get used to Spitfires, Hurricanes and Mosquitoes taxiing by to the hanger; some girls wore earplugs.

One day a Mosquito overran into the hanger and burst into flames. They were mostly wood, so no hope, although fire engines were always on standby, our saviour – our first sad experience.

We were both on “A” Watch, and were to be called the “heavenly twins”; we worked side by side, slept side by side, ate side by side, went on leave together, and were always spoken of as “Rudd” or “Hill”. Christian names were seldom used.

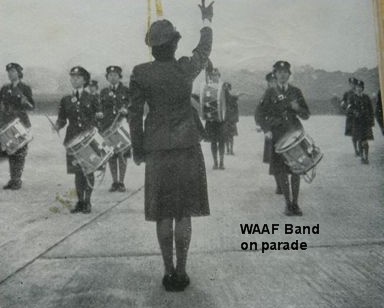

The “Ops” was underground, most of them were, sentry at the door, code number given, which was changed each day. We left our coats, caps etc in the cloakroom. Filed into “Ops”, collected a headset from a row of them, and plugged in next to the WAAF we were taking over from.

When you were plotting in rhythm, she would unplug, disinfect her headset and hang it on the peg. Headsets were adjustable to fit snugly over our ears. Plotting rods were adjustable in length and magnetic. A speaking tube hung round our necks, we were given a position to plug into, and would be responsible for information for that section. Every aircraft in the sky should be shown on the table, as were all air balloons.

At the height of the raids, certain stands were used, 50-

Above the plotting table were two daises; centre top would be the Controller, a RAF Officer in direct contact with pilots. Others would be setting wind velocity against aircraft climbing to find the correct course to send our fighters on. There were several states of aircraft – Release, 1 hour, 30 minutes, 10 minutes, Readiness, 2 minutes, Patrol, Airborne, In Position, and Detailed Raid. Whole squadrons had to be plotted, and directed on its course. Also on the dais were Army Officers in control of their guns – in all of the plotting rooms there was a hive of activity.

We were also detailed P.T. to get fresh air. One day I took the place of a girl who had booked a horse at some riding stables; she could not go, so to save her losing her money, I went. I had to borrow her jodhpurs; we were about the same size. I had never been on horseback – it seemed a long way from the ground! However, she gave me some instructions, heels out, back straight, reins loose, my horse followed hers; if she trotted, we did; if she galloped, we did; I just hung on, and ducked the low branches.

I witnessed a very sad incident at Colerne. We were to be picked up by an Air Force bus, and as it stopped to back and turn, some of us jumped on. One girl, for some unknown reason, was slow going round the back of the bus. The driver did not see her; we felt the bump as it knocked her down and ran over her. The ambulance was there in minutes to rush her to hospital, but sadly she died on the way.

We were all very happy at Colerne, but the time came when we were on the move to Middle Wallop. For some reason unknown, we never warmed to Middle Wallop, so welcomed the call for plotters at Exeter, and volunteered top of the list. Transport awaited us at Exeter Central and we were driven about 6-

Pinhoe was small, with two pubs – “Poltimore Arms” was the one the Army favoured, “Heart of Oak” the RAF – you never found a mix in either pub. Ours had a cat – it seemed to sense when I was there and would appear, thread its way through the people to find my lap, where it could curl up.

Devon was noted for its cider. I didn’t know how strong it was!!! After an evening of many glasses, I was so ill the next morning that I could not move from my bed. Nothing to be sick in but my tin hat!!! The girls kindly emptied it for me, and I have never tasted cider since that evening.

Another incident was when we went to the airfield to a dance on a hot evening. We took a walk along a runway and suddenly planes that were training to tow gliders flew over. They had left the gliders and were trailing the heavy chains – we had to run for our lives!

A large house and park was our destination, a few huts nestled in this park, our new home. There was around 20 beds in each hut, 10 each side. The most coveted beds were the ends ones, under the small windows. The WAAF vacating a hut space would delegate who was to have it after her! I remember this happening, she had written –

To Phyllis Hill I bequeath this corner

Before I go I’d better warn her

There’s not much room to meet

Discuss our Yanks

And how they are sweet!

The wall was covered in such writings.

We took pride in our hut. Each polished the floor space under her bed, we stacked our bedding neatly, kitbags with everything we owned, like sentries to the left and head of each bed. We put our shoes on outside, or walked on dusters, the floor shone like a sheet of glass.

It was a private park, we never saw the public there, and we were marched through it to duty, and marched back again; we never loitered there, or went in any other time; only WAAF “ops” lived in these huts.

The “Ops” building was a short march away, a very busy “Ops”. We would start plotting the “Germans” from the coast of France over the water to our shores, 50-

Airfields, especially “Ops” were a target, they did get some, and WAAF lost their lives. We used to say “if our name is on it…..” I can never remember being frightened – no good to be!

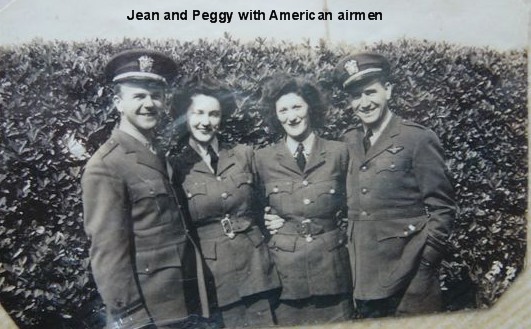

Great excitement – the “Yanks” were here! Right in our “Ops” putting up their own plotting table.

They were young, fresh and smart. Night duty was never the same! We had been issued with navy trousers for night duty. Knife edge creases appeared, starched shirts and collars, make-

Unknown at the time was that they were encouraged to date us WAAF; they knew we had regular FFI inspections and were clean, and they were, I believe, issued with condoms.

However, invitations to their dances were frequent – transport provided, masses of food and drink, we tasted chocolate as never before, we lived life to the full, learnt to Jitterbug, taught them to waltz and foxtrot.

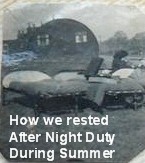

We were lacking sleep; soon to be noted, new rules were issued. We were checked and inspected that we were in bed after night duty especially. A good thing really, cannot keep burning the candle at both ends. One good thing – we never put any fat on!

The Yanks were new to bombs and sirens – who were first down the shelters when the sirens went off? We often never bothered to go down.

While at Exeter, we were sent to Brixham on a course, to see how we got our information. Radar stations on the edge of the cliffs were even more secret; we had a code number or word given each shift, changed each time. We sat in front of a television screen; a needle was revolving picking up information on a grid. It was very tiring on our eyes as, except for the screens, the room was dark. We were pleased when we returned to Exeter.

While at Brixham, though, the first night we went to a dance in the town hall, and danced with every nationality of serviceman. We were surprised that there were only two of us there – until we told the other girls, that is! They said it was out of bounds – we never knew why.

On another night, we missed the last bus from Exeter to the village – we were used to hitching a lift, and a lorry stopped for us. After he started again, we realised that he was drunk as he was driving erratically. At the next pub on the road, he stopped and invited us in for a drink. We said “no, we will wait here” and as soon as he went in, we clambered down and decided to walk – 5 miles at about 10.30 pm. We were late sneaking under the barbed wire that night!

We decided to spend one leave in Blackpool. We had been to the Lower Ballroom, dancing to Reginald Dixon, and were making our way back to our boarding house in Lord Street, where RAF recruits were boarded, when we spied 2 MPs. We slipped down a side street, I don’t know why, just an automatic reaction! But they had seen us and a little way on we came face to face. They thought they had a catch, but when we showed that we were stationed all the way down in Somerset/Devon, they gave up reluctantly and let us on our way.

When I got repeated sore throats, the MO decided that I needed my tonsils removed, so I enjoyed a spell in the Royal Exeter and Devon Hospital. I had to have “junket” which I do not like. (Junket is milk, sugar, rennet, cinnamon, brandy and clotted cream). As I was going on the operating table, the air raid sirens went but no-

I then made the mistake of going AWOL. I was caught, put on a charge and posted to Kirkwall, Orkney. We were to part.

My faithful kitbag was packed, goodbyes made and I started on the long journey from the South coast to the North coast, over the water. It took me two days.

I left the train in London, found a RAF MP, and asked his advice about my destination. He said I would catch a morning train to Scotland, but meanwhile he would take me to a Service hostel for the night; this he did. Of course it was blackout. I had never been to London so was very grateful; otherwise I would have stayed on the station.

I slept well, found my way back and caught the train for Scotland. It was packed – all service people. A Naval lad saved a seat by him for me. I was so grateful, we were to be in this seat all that day and all night, dozing at times, dashing in turn to the loos on the station – one had to guard the seat! We bought sandwiches and tea on the stations we stopped at.

We arrived at the borders the top of Scotland. He was going to a naval base over the water too, so we caught the ferry together. Landing the other side, we found a café, shared a breakfast, said our goodbyes, and went our separate ways. We never even asked names, but I was glad to share the long journey with him. I think it was the Scapa Flow he was based at.

I shouldered my kitbag, asked the way to the airfield, and made my way, longing to wash, and change the clothes that I had worn 2 days and 2 nights without removing. Kirkwall did not have a lot in its favour for me – no trees, windy, bleak, could hardly understand the language, but I was there to stay.

I reported in, was given a bed, a watch I would be on – they were on duty at the time. I got unpacked, managed a bath, met them as they returned from duty, and slept well as usual.

Next morning I joined them for breakfast, and then it was on parade to march to “Ops”. I now had two new plotting tables to learn, one filter for shipping subs etc. This was new area.

About two months later, as I was walking through the camp I spied a WAAF Officer coming my way. As I prepared to pass and salute her, we realised we knew one another as she had been at Exeter. She asked me if I was happy at Kirkwall, I said “yes, but I do miss Exeter”. “Leave it to me” she said. I did not think much about this, but sure enough a few weeks later my papers came – a posting to Exeter. I never saw her again to thank her.

I collected my papers, ship and train passes, said my goodbyes, and made my way to the docks. No companion this time, so a lonely journey, just a repetition of the one to Kirkwall, but in reverses. Two days later I was back at Exeter, same watch, same hut – great rejoicing!!!

It was drawing near to D-

We passed the time mostly playing cards when off duty. One day a low plane flew over our roof tops, bringing us outside to look up to the sky. The plane made a circle, and as it again flew low, it dropped a sack dead on target. We waved to the pilot, clearly visible. This sack contained letters, candies, chocolate and Camel cigarettes – how welcome of them to do it.

This was a time of mixed feelings. We knew “D-

We had other thoughts, too. Back to civilian life. We had lived over 4 years with just a kit bag, 2 sets of uniform, rules to live by. I had a husband to meet whom I had not seen for 4 years.

On his return to this country, he got leave. I did also. We met on Bristol station. He had never seen me in uniform, but there I was in RAF blue like him. We felt like strangers. We had a lot of catching up to do.

We got our demobs, and stayed with my parents. We never went back to the house we bought. We sold it to buy a sweet and cigarette shop, but really fancied a village post office and shop.

We viewed one in a village just outside of Salisbury, Wiltshire, liked it, and moved there. We bought and sold three more village stores, and had a baby boy, before retiring to a flat near Bournemouth.

A few photos remind me of my life in the air force. I am glad to have these memories.

Anyone who remembers serving with any of these young ladies, please contact us we would be delighted to hear from you or your families.

Phyllis’s Photographs

Margaret

Southwest Airfields Heritage Trust © 2017

Back to Top