South West Airfields Heritage Trust

“Preserving Aviation History for Future Generations”

Additional Airfield Defences

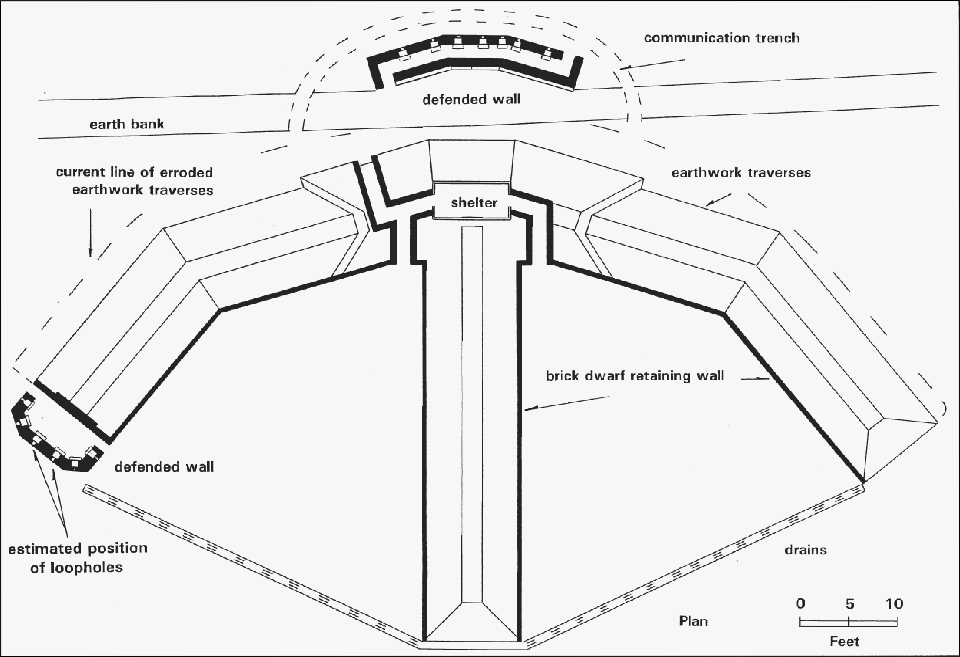

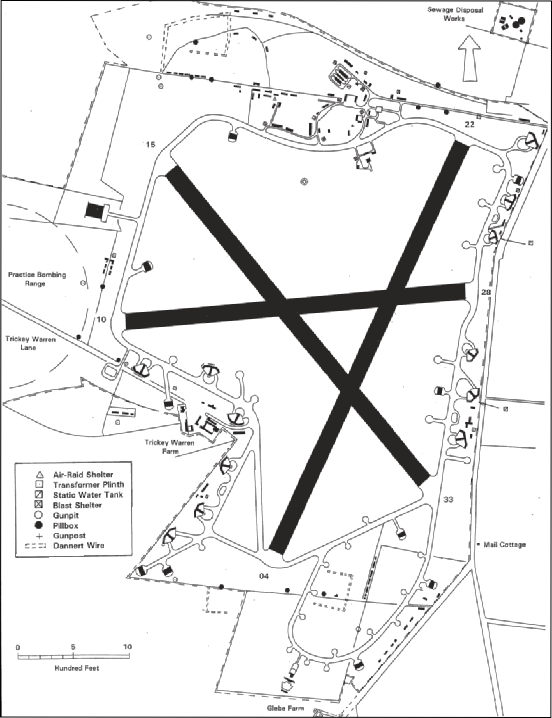

The airfield defences at Churchstanton were numerous and in addition to the walls around the fighter pens, other defences included brick-

A number of brick-

These were semi-

These were located on the main technical sit e and consisted of a 20mm Oerlikon or similar weapon attached to a permanently fixed standard mounting. Also within the airfield boundary and in conjunction with the gunpits were four clutches of pillboxes.

Each group contained three pillboxes and the layout of these are either three in a line positioned along a hedgerow of a field boundary or in the form of a triangle. Those that survive today are of an unusual seven-

One such enclosure in the shape of a “U” was erected in the immediate area around the defence coordination point forming the Battle Headquarters.

Accommodation firstly in the form of Laing huts and later by Nissen hutting, was provided for personnel engaged in airfield defence. These were positioned on the airfield boundaries and therefore close to the defensive positions which the personnel served. Both zig-

In the event of an air-

This form of protection was also used on the RAF communal site, but the other dispersed domestic sites forming the living accommodation and normally used at night had instead, either surface or underground air-

Operational History

1941

RAF Church Stanton later to become Culmhead in December 1943 officially began operations on the 1st August 1941 and closed on the 6th August 1946, although on the 9th June 1941 half the aircraft of 307 and 504 Squadrons stationed at RAF Clyst Honiton (Exeter) had been dispersed at church Stanton in anticipation of moonlight raids

Thus the Bolton Paul Defiants and Hawker Hurricanes of these two units became the first aircraft to make use of the new, but incomplete airfield.

However The first squadron to officially operate from the Airfield, was the polish Squadron 316 also equipped with Hawker Hurricanes.

However even at this stage construction of the runways was still in progress, and the site was not even connected to the mains water supply. To the extent that on the 3 August, a taxing aircraft had the misfortune of colliding with a steamroller engaged in finishing off the runways !

None of this prevented the Poles from flying operations and at 10.30 hrs. on the next day, August 4th Hurricanes Z2585 and Z2702 took off on Churchstanton’s first operation —a convoy patrol lasting 1.5 hours.

This Patrol would be the first of many carried out by numerous squadrons from the Airfield. Although by the time Church Stanton opened the threat that it had been created to counter, was now diminishing. As a result, patrols from Churchstanton were instead carried out for the protection of shipping convoys, as well as the escorting of both RAF and USAAF bombers in hitting targets in north-

Some Squadrons would be there for a few months with some for a few weeks. But the main activities remained the same protection of convoys and the escorting of bombers to France and back

For Example On 6 August 1941, 316 Squadron sent a force of eight Hurricanes to cover the return of two of the RAF’s new Flying Fortresses from a raid on the German battleships then lurking at Brest.

Although Churchstanton would normally house only one fighter squadron during its first year of operations, a second Polish Hurricane unit was also based here for the first month. This was 302 Squadron, which immediately joined in with the convoy patrols and bomber escorts sometimes making use of the advanced bases at Bolt Head, Ibsley and Portreath

See 316 Squadron remembered click picture below to activate link

Tragedy stuck on 24 August 1941, when Hurricane Z2913 “WX-

The aircraft was returning after carrying out a convoy patrol and it was seen to pass very low over the Merry Harriers Inn with obvious engine trouble. It then crashed into a field beyond and burst into flames, whereupon and with great courage, two local people, Charles Smith and William Harris extricated the pilot, only to find that he was dead.

On 26 August, 12 Hurricanes of 302 Squadron joined a similar number from 317 Squadron at Exeter and flew an offensive wing patrol over the Cherbourg peninsular.

By the autumn of 1941 the Hurricane IIA was no match for the enemy fighters then being encountered over France and in mid-

Operations with this aircraft began on 1 November and on the 8 November they flew from Redhill to join the 11 Group Wing to take part in “Circus 110” over Lille.

The codename Circus was given to operations by the RAF during World War II where bombers, heavily escorted by fighters, were sent over continental Europe to bring enemy fighters into combat. These were usually formations of 20 to 30 bombers escorted by up to 16 squadrons of escort fighters. Bomber formations of this size could not be ignored by the German Luftwaffe and resulted in bringing the enemy in to battle.

These were hazardous operations and in the course of this raid the RAF lost 17 spitfires in total to Jagdgeschwader( Fighter Group) or JG2 including the Commanding Officer, of Churchstanton who was lost with two other Churchstanton Spitfires which were badly shot up.

Quite undaunted, the squadron persevered and on 12 December moved up to Northolt to defend the capital.

316 Squadron was replaced by 306, which became the third Polish unit to be based here being fresh from a rest period in the north-

Once there, the 306 took over a complement of Spitfire's VB left behind by No. 316 Squadron. This time, the unit became part of the Second Polish Fighter Wing, commanded by W/Cdr Witorzenc.

From Church Stanton, the 306 started to fly patrols, slowly joining more often in offensive sorties over France. In those flights the unit was credited with several panes shot down, for the loss of one pilot, F/Lt Zielinski, Flight "A" commander.

For both of these 306 Squadron operated as part of the Exeter wing, using Bolt Head as a temporary base to maximise their range.

On the 18 December, the first raid code named Operation Veracity took place and 306 Squadron claimed two Me. 109’s for no loss. On the second Veracity raid, however, which took place on 30 December, one Spitfire was lost, although the squadron was able to claim four Messerschmitt’s destroyed.

1942

At first light on 12 February 1942, the 10 Group fighter airfields at Exeter and Warmwell were both bombed, and when 306 Squadron was scrambled to intercept the raiders, it had not yet been established that these raids were in connection with the attempted escape of the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau.

The two ships had not only left their lair at Brest undetected but by 8 am were already level with the coast of east Sussex in their audacious dash up the English Channel en route for Germany.

Most of the fighter stations in 10 Group were engaged, directly or otherwise, in attacks on enemy shipping and on 15 March for example, the 306 Squadron Spitfires joined forces with their Polish compatriots of 317 Squadron at Exeter to take part in “Roadstead 17”. This involved escorting a party of five Hudson’s making a raid on enemy vessels off the Ile du Batz.

Roadstead operations consisted of Low-

Many operations of this kind were carried out during the summer months, typical examples, on the 16 April, had 306 Squadron flying from Tangmere with 302 (Harrowbeer) and 308 (Exeter) for “Ramrod 20” to Le Havre and a “Rodeo” to Gravelines.

Ramrod missions were similar to Circus, but with intention of destroying a target and Rodeo was fighter sweeps over enemy territory

The first quarter of the year was filled mostly by training and patrols. In March, few offensive sorties were flown, but no major events were recorded in books. Several scrambles and more changes in pilot roster marked this period.

Only in mid April, with the change of weather, the monotony was over. On 12th, that month, the pilots of the 306 flew an air show over the industrial complex of Weston-

The Circus 123 started with accident during mid-

On April 16, the 306 flew two Rodeos over France and during the morning none, P/O Sologub shot down two Bf109s. Later, with five confirm kills he became an ace. The rest of the month for the 306 was very busy, with several dogfights over France with Germans, which resulted with the loss of only one pilot and several claims.

On May 1, the section of the unit, stayed in readiness on advanced airstrip of Bolt Head. The location was a favourite target of low-

Two days later, the reorganization of Polish Wings, brought the 306 a rest at RAF Kirton-

The first quarter of the year was filled mostly by training and patrols. In March, few offensive sorties were flown, but no major events were recorded in books. Several scrambles and more changes in pilot roster marked this period. Only in mid April, with the change of weather, the monotony was over.

On 12th, that month, the pilots of the 306 flew an air show over the industrial complex of Weston-

On April 16, the 306 flew two Rodeos over France and during the morning none, P/O Sologub shot down two Bf109s. Later, with five confirm kills he became an ace. The rest of the month for the 306 was very busy, with several dogfights over France with Germans, which resulted with the loss of only one pilot and several claims.

On May 1, the section of the unit, stayed in readiness on advanced airstrip of Bolt Head. The location was a favorite target of low-

Two days later, the reorganization of Polish Wings, brought the 306 a rest at RAF Kirton-

Balloons ! & The Royal Aircraft Establishment arrives from Farnborough

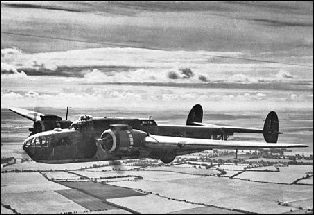

Meanwhile, a new and little known experimental unit had been transferred to Churchstanton in order to relieve congestion at Exeter. This was a research flight, which had been detached from the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough at the outbreak of war to carry out secret trials in the West Country in association with the Washington Singer Laboratories in Exeter. By March, the flight had made its home at Churchstanton and brought about half a dozen aircraft with it — at least one Wellington, two Hurricanes (including AF979), some Fairy Battles and it is believed, a Bristol Blenheim.

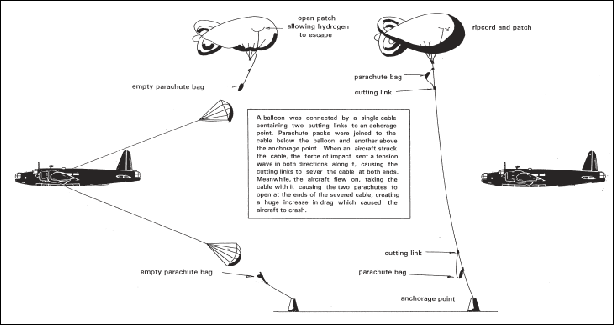

One of the flight’s principal tasks when flying their variety of types of aircraft was to carry out “impact flights” flying into cables suspended from barrage balloons. Experiments were first conducted on cables with a strength of 3.25 tons as used by British barrage balloons and it was assumed that the German cables would of a similar strength.

On the discovery that the Germans used a 1-

The aircraft were frequently damaged, and some were even destroyed, on 23 March 1942 for example, after hitting the cables at Pawlett, Wellington P9210 broke up in the air, the pilot did however escape by parachute. On 18 September, a Hurricane’s radiator was holed in the impact, with the result that the engine seized and a crash landing had to be made.

On another occasion, in April 1943, two Hurricanes made a joint sortie into a “Projected Salvo” fired from a site at Watchet, and were both damaged in the process. In conjunction with the impact testing, the flight also played an important role in the development of other systems involving the use of cables, such as the Long Aerial Mine.

This was towed by a bomber with the aim of blowing up a fighter in pursuit. Other work done included the dropping of wind armed bombs, various parachute designs, and the testing of bombs fused by photo electric cells and proximity pistols. Experimental cable cutting was also carried out at Haldon Racecourse, where a catapult device had been specially set up for the purpose.

By 1943, however, enemy barrage balloon cables were posing only a very limited hazard to Allied bombers and accordingly, the amount of experimental work was reduced. So on 12 March 1944, the detached flight closed down and the flight then transferred to RAE Farnborough.

Meanwhile on 3 May 1942, another change had taken place with the departure at 13.00 hrs. of 306 Squadron which left for Kirton-

For a period of four weeks their place was taken by another RAF Spitfire unit, 154 Squadron. Equipped with Spitfires, it moved to Churchstanton in May for convoy escort duties before moving to Hornchurch in June

On 8 June the Czech Spitfires of 313 Squadron arrived for a twelve month period, making them one of the stations longest residents.

On 17 August 1942, 313 joined their compatriot squadrons from Exeter (310) and Harrowbeer (312) in making a sweep to Cherbourg alongside two USAAF B17s. This mission was a diversion for the first bombing raid mounted by the USAAF against the marshalling yards at Rouen. USAAF fighter aircraft also made their first appearance at this time

On 9 September, the first P38 Lightning to be seen at Churchstanton landed here from its base at Ibsley.

Offensive operations were increasingly flown from advanced bases and between 26 to 29 September 1942 the squadron was detached to Portreath to take part in “Operation Crucible” — a USAAF B17 raid on Brest. Their place was taken by 12 Group Spitfires from Kingscliffe. 10 Group Spitfires were now required to fly from 11 Group bases.

Following a mission from West Malling on 8 October, 313 Squadron was sent to the American fighter base at Debden in Essex. Here they joined the rest of the Exeter wing to carry out a diversionary sweep off the Dutch coast in support of “Circus 24”—a USAAF raid on Lille.

With the completion of two sets of aircraft fighter pens to house two fighter squadrons, a second unit arrived (312 Squadron) at Churchstanton on 10 October 1942.

On 15 October, 312 and 313 Squadrons took part on a joint mission to escort six Hurricane fighter bombers in an attack on enemy shipping off the Brittany coast. Offensive sweeps continued, and on 28 October, 312 in addition to escorting a force of Hurricane fighter bombers, attacked and damaged a locomotive.

From November 1942, escort duties were undertaken in support of both RAF and USAAF bombers. Typically raids took place on targets in Brest, Lorient, St. Malo and St. Nazaire. Again many missions were conducted from 11 Group airfields for example, in December, two raids took place from the Tangmere Sector to shepherd B24s back from Abbeville and Romilly.

Church Stanton, August 1941. Flight B Hurricanes Mk IIA: SZ-

302 Sq Spitfire VB WX-

The second squadron's commander S/Ldr Piotr Laguna.

A staged photo of Nowakiewicz with Spitfire.

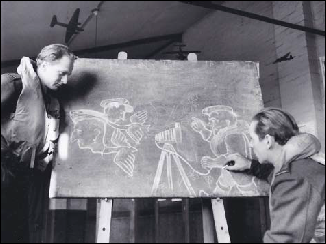

Polish officers of 306 Squadron drawing Cartoons (of the official photographer?) in a flight office, RAF Church Stanton (Culmhead)

1942 (© IWM CH4799) These images also capture model aircraft, suspended from the roof of the flight office, which were used to help pilots recognise different types of aircraft

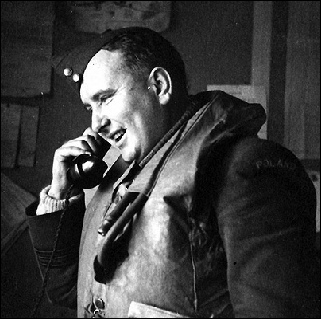

Sergeant Witold Krupa of 306 Squadron

wearing his ‘Mae West’ life jacket, RAF Church

Stanton 1942 (© IWM CH4795) Flying Officer Witold Krupa has an aircraft silhouette on his Mae West life jacket, and the names ‘Mollie’ and ‘Sheila’

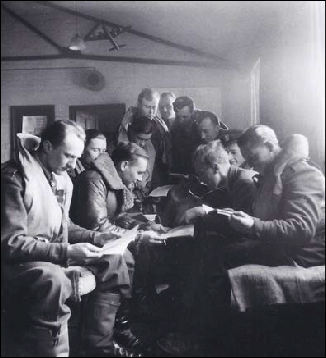

Polish pilots of 306 Squadron having English

lessons in a flight office, RAF Church Stanton

1942 (© IWM CH 4790)

Alfred Krzysztof Wlodarski taken whilst with 316 (Polish) Squadron

306 Armourers loading Ammunition Culmhead

312 Location unknown Possibly Culmhead

313 Czechoslovakian Squadron

312 CZECH squadron -

312 CZECH squadron Location unknown

Squadron Leader Antoni Wczelik, the CO of No. 306 Polish Fighter Squadron, briefing his pilots on the next operation with mascot in attendance at RAF Churchstanton, 26-

From left to right -

Flight Lieutenant Tadeusz Czerwiński, the CO of "A" Flight of No. 306 Polish Fighter Squadron, and Flight Lieutenant Stanisław Skalski, the CO of "B" Flight, with the Polish national emblem. RAF Churchstanton, 26-

Airmen of No. 306 Polish Fighter Squadron in front of one of their Spitfires at RAF Churchstanton, 26-

306 Squadron Culmhead

Culmhead Note damaged tail

306 Squadron Culmhead

Spitfire Vb DUZ (AR614), was piloted by 312 Squadron Leader Tomas Vybiral and stationed at RAF Culmhead October 1942 to June 1943 and is still flying today in the United States

(Via the Flying Heritage Collection)

June 1943 saw a total changeover of the units based at Churchstanton. First of all, on the 24th, 14 Harrows arrived from Skeabrae with 234 Squadron, whose Spitfire Vs flew in to replace 312 Squadron. They were followed four days later by 66 Squadron from Orkney to replace 313, and finally, on 30 June, 504 Squadron moved across from Ibsley. The latter unit was sent here because 234 had been selected for service overseas and was already making preparations that included the acquisition of nine Spitfires in tropical camouflage.

They departed on 9 July, the pilots for Honiley and the ground crews for the transit camp at West Kirkby. Their final destination was a closely kept secret and in the event, the move never actually took place.

Meanwhile, during the summer of 1943, 66 and 504 Squadrons were engaged in bomber escort duties.

On the 25 July for example, they operated from Coltishall escorting Mitchells to Amsterdam in the morning, and Bostons to Schipol airfield in the afternoon. Other raids were flown from Martlesham Heath to support USAAF B26 raids and from Churchstanton, the Spitfires guided Bostons to Rennes and Whirlwinds to Brest/Guipavas airfield.

In mid -

For over a month the airfield at Churchstanton was conse quently deserted, disturbed only by the occasional diversion, as on 19 August when twelve USAAF P47s flew in.

Regular flying began again in mid September, when 131 and 165 Squadrons moved in from Redhill and Kenley.

The latter unit had just received Spitfire IXs and soon, 131 became similarly re-

On 1 December, flying from Ford, the squadrons escorted a formation of 54 B26s to Cambrai/Niergenies.

Change of Name

Unfortunately, as time had gone on, the “Churchstanton” address had been regularly confused with other RAF stations having similar names, notably at Church Fenton and Church Broughton.

In mid-

In the course of this 165 Squadron “bounced” five rocket carrying enemy fighters as they were about to attack and destroyed four at no loss to themselves.

1944

The lack of range was always a problem for the Spitfire so during “Rodeo 61” on 5 January 1944, the aircraft had to use 45 gallon underwing tanks to escort B17s returning from France. Increasingly, in the early weeks of the year, the wing used bases such as Kenley and Ford for their Ramrod operations.

On 10 February they moved eastwards to Colerne and again left Culmhead vacant for a few weeks.

On 10 March, to cover the major landing exercises by US forces in south-

This unit was newly equipped with the high speed Spitfire XIV, and as well as carrying out shipping searches they escorted Typhoons making attacks on E-

Handley Page Harrow -

504 at Exeter

Aerial Shot of the P47s at Culmhead & below a picture of P47s (not Culmhead)

131 Squadron -

Spitfire VII of 131 Squadron with long range drop tank at Culmhead during the summer of 1944.

Meanwhile, taking the place of the RAE Flight, which had recently been disbanded, 286 and 587 Squadrons moved their headquarters here in April. The former unit, which provided target practice facilities for anti-

In April, the Fleet Air Arm arrived for a four week stay when 24 Fighter Wing flew in, consisting of 887 and 894 Squadrons, equipped with Seafires. Like their RAF predecessors they flew shipping reconnaissance patrols along the French coast, also providing escorts for Typhoons.

One of these on 3 May was “Roadstead 102”, when the large fighter bombers succeeded in beaching an enemy destroyer. On 15 May, the Seafires returned to Northern Ireland and in due course embarked on HMS Indefatigable and sailed to the Far East.

The departure of the Navy heralded the last series of fighter squadron changes at Culmhead and on 16 May, as 610 Squadron left for Bolt Head and Harrowbeer, 616 Squadron moved in from Fairwood Common. The new unit was one of those equipped with the high altitude Spitfire VIIs and was joined a week later by the similarly equipped 131 Squadron and 126 Squadron which had the Spitfire IXs. As the date for the invasion was now drawing near, all three units started an extensive series of “Rhubarb” attacks on railway targets at places such as Dinan, Guignamp, Lamballe and Rennes.

On D-

Whilst on 18 June, 126 and 616 Squadrons escorted a force of Coastal Command Beaufighter’s on “Roadstead 143”.

Gloster Meteor arrives at Culmhead

It was in July 1944 that Culmhead was the scene of an event of enormous historical importance — the delivery to 616 Squadron of the very first jet propelled aircraft to enter service with any of the Allied air forces.

During the afternoon, 12th July 1944 – two Meteors (EE213 and EE214) arrived from Farnborough to No.616 Squadron based at Culmhead. These two were not fully operational and were used for training purposes. Although both aroused much interest, they were closely guarded throughout their stay at Culmhead

Some accounts say that the first aircraft to arrive at Culmhead was EE215 followed a day later by EE216 and EE217, however our timeline currently references arrivals as detailed in 616 Sqn records. Taken from http://www.manstonhistory.org.uk/jet-

These Records go on to say that on 23rd July 1944 – five more Meteors F.1s (EE215, EE216, EE217, EE218 and EE219) arrived at Manston from Farnborough not Culmhead . So we have chosen to accept 616’s record as the true account

As this was some months before the Me 262 entered service, which was not until October 1944. This qualified the No. 616 as the world’s first operational jet fighter squadron and Culmhead as the first operational Airfield that Jets first flew from. Although only one week later on 21st July 1944 – The first two Meteors (EE213 and EE214) were transferred to RAF Manston , where they would later be joined by the additional meteors direct from Farnborough to attack the V1 Flying bomb.

Following a number of near misses and problems with aircrafts cannon jamming on August 4th, Flying Officer “Dixie” Dean scored the Meteor’s first kill by tipping a V-

The squadron eventually accounted for fourteen V-

No. 616 Squadron exchanged its F.Mk Is for the first Meteor F.Mk IIIs on December 18, 1944.

By now 131 Squadron had become the last operational fighter unit on the station and in August it flew the last of the “Rodeo” missions from Culmhead. While using Tangmere, Ford or Manston, as advanced bases the squadron was mainly used to escort forces of Halifax’s and Lancaster’s on daylight raids.

By the end of August 1944 the battle lines on the Continent were advancing eastwards and accordingly 131 Squadron was transferred to Friston in Sussex bringing an end to Culmhead’s operational career as a base for fighter aircraft.

For several weeks the airfield was used as a temporary base for Fleet Air Arm aircraft, this time 790 Squadron. The new unit provided flying facilities for the Fighter Direction School, which trained naval fighter controllers.

For this task, the squadron used a mixed fleet of naval fighters and twin-

At the end of September both 790 and 587 Squadrons moved out and for many weeks the airfield once more lay vacant. Following the heavy losses taken by the Allied forces in the Arnhem operations in September, priority was given to rebuilding the strength of the glider pilot units and the three Glider Training Schools were placed under considerable pressure.

At one of these, 3 GTS at Stoke Orchard and its Northleach satellite, progress was being severely hampered by the unserviceability of the grass airfield surface at both sites. Zeal’s was first chosen as an alternative and served for a few weeks until its grass surface too, had become unavailable whereupon it was decided to find a spare airfield with runways.

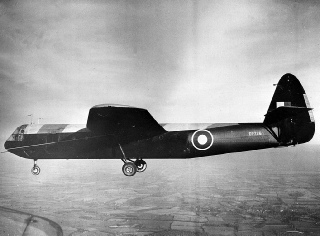

Culmhead was duly re-

1945

A month later, Exeter was made available as a replacement headquarters station for the school and by the end of January, the whole of 3 GTS was transferred there. Culmhead was now to become merely a satellite once again, but was chosen as the home of the newly reformed Glider Instructors School. This operated as part of 3 GTS and was responsible for the appearance at Culmhead of a small fleet of seven Albemarle’s and a similar number of Horsa gliders together with a detachment of Master tugs and Hotspurs.

3 GTS now had the problem of manning a fair sized station with a very limited number of personnel, but despite the difficulties its instructors set about the final task of training staff pilots to man the Glider Training Schools.

The airborne forces operations in connection with the Allied crossing of the Rhine in March 1945 were soon to be the last in Europe in which gliders were used in force. As the schools were also involved in preparing for similar campaigns in the Far East, there was no let-

Work was still under way as VE-

This was not quite the end, as in August 1945, the airfield was used as a out based storage site by 67 maintenance Unit, to hold some of the vast quantities of equipment and vehicles which had now become redundant and awaiting disposal.

1946 and Post War

Twelve months on this role had been completed here and in August 1946, RAF Culmhead was finally closed.

1950’s

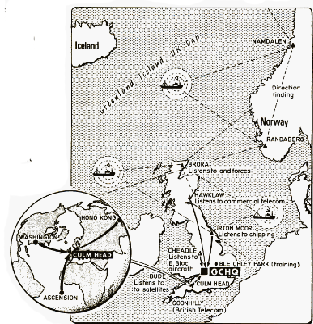

From the 1950s, the site was partially re-

This enabled Culmhead to intercept long range signals and short wave high frequency transmissions from all over the world though mainly from the three GCHQ STATIONS at Washington, Hong Kong and Ascension Island. See Map

These were then sent to GCHQ at Cheltenham in Gloucestershire where they were deciphered

In 1999 GCHQ closed down their unit and removed their aerials with their building in the centre of the Airfield being turned in to Business park

Today most of the runways are buried in vegetation and overgrown although many of the derelict buildings still remain and provide a fascinating and evocative insight as to what took place there.

Following work by the Phillips family who still own the Airfield, the Area of Outstanding natural beauty and the South West Airfields Heritage. Trust. The control towers and fighter pens have been designated as Scheduled Ancient Monuments and are included in the Heritage at Risk Register produced by English Heritage.

TOURS

Tours of this Airfield are available through SWAHT and there are plan to develop a Heritage centre on the site. See Airfield Tours & Talks Link

Further Information

https://fcafa.com/

Links

Gloster Meteor EE214 that landed at Culmhead

A Gloster Meteor F.1, of 616 Sqn, coming in to land at Manston, Kent, during the summer 1944.

A Gloster Meteor F.1s of 616 Sqn, based at Manston, Kent, in flight over the countryside between West Hougham and Dover, ever ready to intercept V-

Gloster Meteor F.1 EE227/QY-

Meteor F.1s of 616 Sqn, with EE219/D in the foreground, lined-

Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle Mark I

Horsa Glider

Miles Master Tug

Hotspur Glider

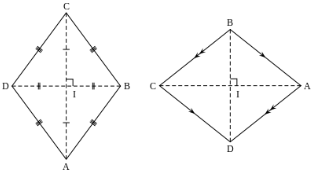

Two Rhombi

Rhombics at Culmhead

Summary

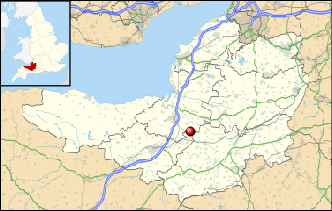

Location Culmhead, Nr Taunton, Somerset

Opened 1941

In use 1941 to 1946

AIRFIELD HISTORY

Background

From the summer of 1940, during the Battle of Britain, RAF Fighter Command was under immense pressure so that towards the end of the battle, only three squadrons of day fighters were available for the defence of Devon and Cornwall. This was despite the location of vital strategic targets such as the naval base at Plymouth.

In addition the area also lay right in the path of enemy raiders flying from northern France and heading for targets in South Wales, the Midlands and the North West.

Even if more fighters were available however, the airfields to house them were not, and it was obviously essential to find new sites as a matter of urgency.

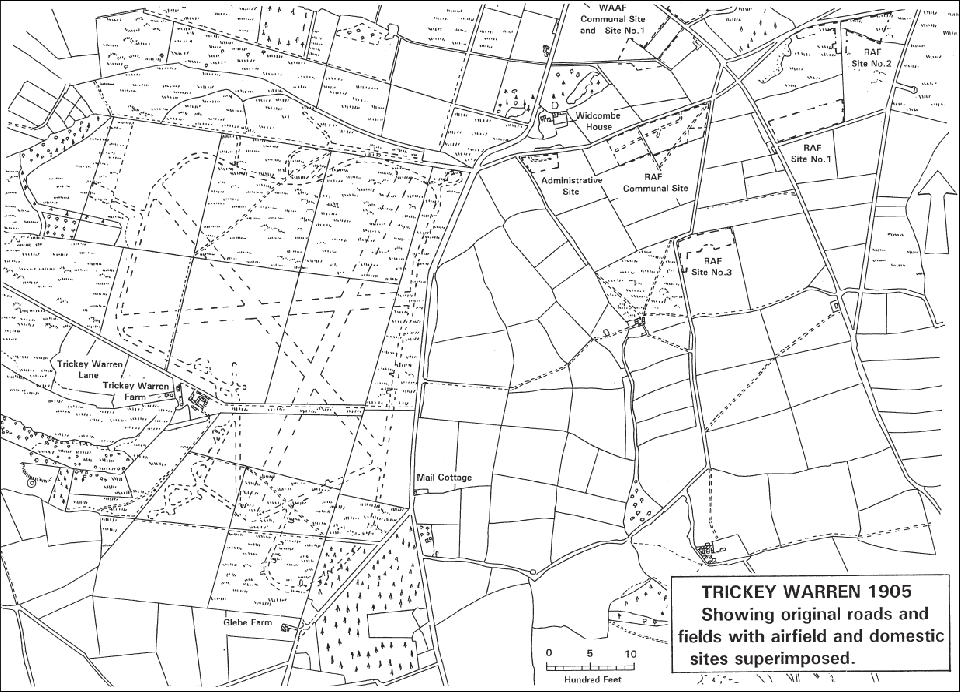

Since so much of the West Country was unsuitable being either the Somerset Levels or steep wooded valleys, the location for a new airfield was not easy. An early choice was a fairly level area of high ground at the east end of the Blackdown Hills, lying in Somerset but close to the Devon border. At the south end of the site lay Trickey Warren Farm and to the south-

Taunton is six miles to the north, and the nearest point on the south coast at Seaton, is only sixteen miles distant. RAF Churchstanton with a height above sea level of 894 feet, became the second highest airfield in the country. The highest airfield at 969 feet above sea level was Davidstow Moor in Cornwall.

Before July 1940, this area of land had already been listed by the Air Ministry as an emergency landing ground and full requisition soon took place for the development of the site as a satellite airfield in 10 Group (that part of RAF Fighter Command covering the south-

The 520 acres of land covering the airfield including Trickey Warren Farm was owned by the Phillips family of Burnworthy Manor. At this time, it was intended to use the new base as a forward airfield for the Fighter Sector centred at Colerne near Bath.

Construction

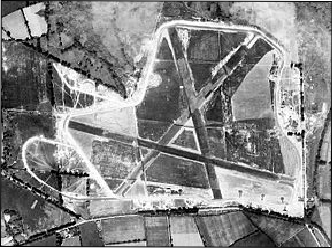

In November; 1940 a contract for the construction of three tarmac runways had been awarded to LJ Speight and Partners Ltd. Work commenced almost immediately and although delayed by poor weather that winter, it was well advanced by the following June. In the meantime, the site had been relocated to serve as a satellite station for the Sector airfield at Exeter, the principal fighter station in the area and with Which it was closely associated throughout its operational career.

The airfield boundary followed existing public roads and field boundaries. Trickey Warren Farm and surrounding land was requisitioned, and a closing order served on Trickey Warren Lane. This lane became the centre line for a practice bombing range contained within the surrounding fields. By the time that the station officially opened on 1 August 1941 the decision had been made to equip it as an operational fighter station in its own right, and not as a satellite.

Layout

Out of a total of 444 RAF airfields with hard runways only 111 had runways constructed of tarmac. This figure excludes the 30 airfields built for the Ministry of Aircraft Production and Royal Naval Air Stations.

Drains to take rain water away from the runways were provided along all three runways with catchpits positioned at intervals. No airfield lighting was provided.

The fighter pens built along the south-

Furthermore, the south-

The airfield would have presented an attractive target for capture by German paratroopers for use as a forward airfield for operations against the military targets at Bristol, Exeter and Taunton. The fighter pens along the south-

At least two pens belonging to the other groups along the eastern perimeter track were also defended but these were designed only to contain the enemy forces within the airfield boundary and prevent them from dispersing into the local area.

In all cases the plan-

Click pictures below for Video links

Fighter Pen

Above & below Pill Boxes

Fighter or Dispersal Pens Type “B” FCW 4513 Plan showing defence positions in Pen

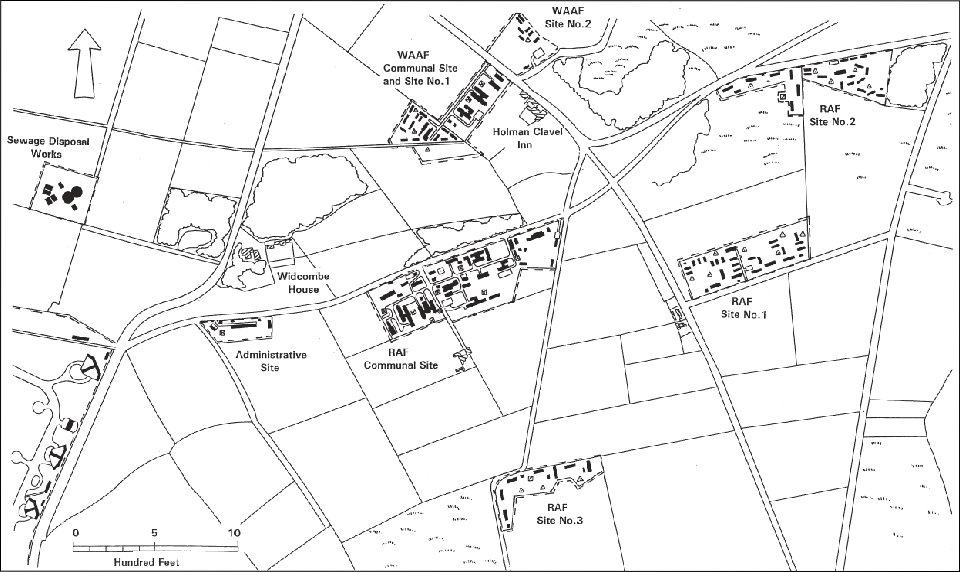

Plan of Domestic Sites based on Air Ministry Plan 4997/45

Aircraft Hardstandings and Fighter Pens

At the southern end of the inner perimeter track was a aircraft dispersal area in the form of an outer loop, this was designed to prevent congestion on the inner (main) perimeter track and contained 15 small hardstandings.

A number of larger hardstandings were also provided around the inner perimeter track. Eventually eleven Blister type hangars were dispersed around the inner and outer perimeter tracks but one of these was probably removed c1943 to be replaced by a 14-

Twelve of the larger Type “B” fighter pens were built here, each designed to house two aircraft of a size similar to that of the Bristol Blenheim. To minimise the effects of an enemy attack from the air, fighter pens were positioned in four groups of three pens.

One group accommodated one flight of six aircraft, therefore, a total of 24 aircraft under scramble conditions could be protected inside the pens at once. Two flights were located on the east side of the airfield and two flights on the west side.

To counter the effects of bomb blast, the pens were based on the Type “B” fighter pen with blast walls and this was achieved by two different methods.

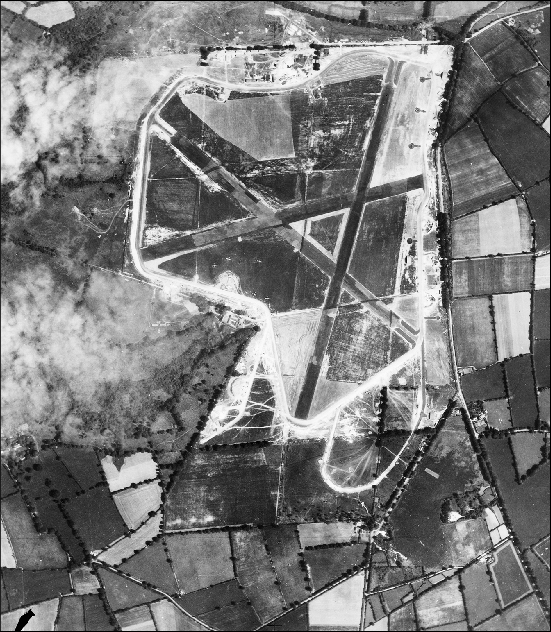

Trickey Warren on the 1905 Ordinance Survey Map with the Airfield and domestic sites superimposed

Runways

Designed from the beginning, on the 3 Grass strip, principle. With each strip 200 yards wide and approximately 60 degrees to each other. Hard surface runways were to be built along the centre of the strips and connected by a hard surface perimeter track with a width of 50 feet.

The chosen runway lengths were over and above of those recommended in March 1941 for a typical night fighter station

.

Runway 04–22 — 1410 yards by 50 yards

Runway 10–23 — 1320 yards by 50 yards

Runway 15–33 — 1130 yards by 50 yards

For reasons of light wear and tear by fighter aircraft, local conditions and the availability of local hardcore from Triscombe quarry, three tarmacadam runways were specified instead of the universal practice of concrete.

This included an eight-

An undercoat of a two-

•A final sealing coat was obtained by a sealing coat of hot tar with a binding of between 0.125 to 0.250-

Ministry Plan of Airfield

Buildings

The construction of the airfield accommodation at Churchstanton was in two phases, the first started in the winter 1940/41 and encompassed the original planning for a satellite airfield. This involved the construction of temporary brick structures using bricks from the Wellington brick works.

This included a few specialist buildings such as a fighter satellite watch office and decontamination facilities. At this stage only essential buildings and structures were built on the airfield site with the majority of them being erected on the dispersed sites.

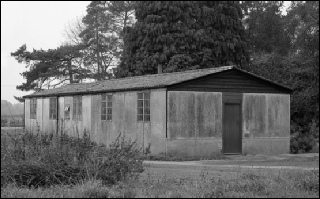

Many were in the form of a new Ministry of Supply prefabricated building known as the “Laing hut”

These were supplied by the Air Ministry to various airfields from January 1941 when production started at Elstree, Herts. Almost simultaneously, building for the upgrading of the airfield to a fighter station in its own right commenced, including many new structures to the latest standard of temporary brick buildings.

At least one of these, the new watch office replaced the earlier satellite example and firmly established RAF Churchstanton as an operational fighter station.

Although an operations block was not built, a station intelligence and briefing room was provided for briefing and debriefing of pilots before and after a mission. Fighter operations were planned from the Sector operations block at Exeter.

The planning and layout of Churchstanton in its final form as a fighter station of the early part of the war was typical of the period with technical buildings located on the airfield site. In anticipation of concentrated bombing, a policy of dispersed layout was introduced so that domestic accommodation was separated from the airfield.

These were provided within six dispersed sites located in the local area to the north-

Below a picture showing the Airfield and the dispersed Sites

Rhombics at Culmhead

The Watch office at Culmhead Today

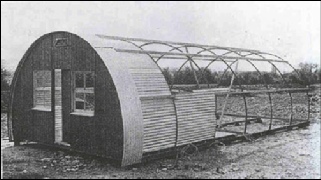

An example of a wood and asbestos Laing Hut -

An Example of a Nissen hut -

For more information on Nissen Huts go to

Many were erected on the dispersed sites to supplement the existing Laing huts. Two new sites were added in late 1941 for WAAFs and eventually accommodation was provided for over 1400 personnel consisting of 1,136 RAF and 301 WAAFs. A further two sites were added to the six already established but these were located at some distance further north towards Taunton. Both used existing houses with one functioning as a sick quarters, while the other became a large officers’ mess.

A water supply taken from the natural springs of the river Culm was piped to a large static water tank and pumping station located on the administrative site. A booster pump house on the main communal site, pumped water from here to another static tank and finally to a high level water tower. In addition, static water tanks were provided close to groups of buildings for fire-

Sources of information, Text & Photographs

-

-

Project Report by Hazel Riley

-

-

-

-

-

-

1943

On 26 January they escorted a force of twelve Venturas of 21 Squadron on a raid to Morlaix for 10 Group “Ramrod 49”.

“Tip and Run” or Hit and run enemy raiders were now becoming an increasingly frequent menace on the south coast and the Czech Spitfires were amongst those scrambled to intercept them. Most of these took place at low level

On 19 February 1943, a 313 Squadron Spitfire while over Newton Abbot, intercepted three FW 190s at 23,000 feet. One week later, eight FW 190s made an attack on Exmouth and were encountered by chance by a flight of 313 Squadron.

The Spitfires were returning to base and were low on fuel, but succeeded in directing two 266 Squadron Typhoons to the intruders that resulted in two Focke Wulfs being shot down. To keep track of the movement of enemy shipping and to select targets for attack, the Churchstanton squadrons played a regular part in the continuous shipping reconnaissance campaign off the Brittany coast and the Channel Islands.

On 30 March, 312 joined 504 (Ibsley) and 602 Squadrons (Perranporth), on a sweep from Ushant to Barfleur. Bombing raids were mounted.

On 4 April, while using Portreath as a advanced base, the Czech wing escorted twelve Venturas of 21 Squadron to Brest. As well as British and American bomber formations, the Spitfires regularly escorted Westland Whirlwinds making fighter bomber raids.

A typical example took place on 10 April, during the 10 Group raid “Circus 22” when the target was the airfield at Brest/Guipavas.

Another operation on 3 May, involved an armed shipping reconnaissance when 313 joined 310 Squadron from Exeter and escorted six Whirlwinds of 263 Squadron (Warmwell) on a sweep off Guernsey and the Ile du Batz.

The Spitfires themselves were now equipped to act as fighter bombers and on 23 June, 126 Squadron, flying from Bolt Head, mounted “Ramrod 144”, an attack on radar stations on the French coast. Ten days later this squadron moved on to Harrowbeer.

However Help was still needed from time to time by 11 Group and Culmhead again responded by sending Spitfires to Ford on 12 July to escort a daylight raid by Lancaster’s.

Southwest Airfields Heritage Trust © 2017

The Double Parachute Link System developed by the RAE at Pawlett Hams